September 1, 2023

By Steve Blumenthal

“Cycles are the most important thing.“

– Britt Harris, CEO and CIO, The University of Texas/Texas A&M Investment Company

First, let me begin by wishing you a fun-filled weekend. As summer comes to an end, I hope this note finds you on the beach, by a lake, in the mountains—or somewhere you enjoy the most, relaxing.

Let’s keep this week’s OMR note brief. After reading Mauldin’s “The Science of Cycles” last week, I called John and told him I thought it was one of his most important letters to date. Then, this last Monday, John and I had the privilege of speaking with Britt Harris, President, CEO, and CIO of the University of Texas/Texas A&M Investment Company (UTIMCO). Important talk of the cycles indeed!

Britt has led several of America’s largest, most successful, and most innovative investment organizations, including Bridgewater Associates, where he was CEO for a time. In addition to his work at UTIMCO, he is a member of the President’s Working Group for Financial Markets and an advisor to the New York Federal Reserve. Britt is smart, welcoming, and balanced, and he listens intently. We are really going to need his private-sector expertise in those public-sector discussions.

Britt said on our phone call, “Cycles are the most important thing.” He added, “This is what matters most, but it is what people care less about. It is what people need to know.”

As we think about cycles: A turning point occurs when hope is lost. Right now, hope still exists. Hope in the Fed’s (monetary policy) and Governments (fiscal policy/QE3) ability to bail us out. Trust in our leadership, our legal system, and our media. Britt said, “Hope is the bridge… people don’t push back until hope is lost.”

Hope is fragile. We may be nearing a turning point.

Grab your coffee and find your favorite beach chair. I begin with a few “bottom line” thoughts, then share John’s post in full. You’ll also find links to additional resources if you’d like to dive deeper (which I encourage you to do). Finally, I’ve become a very big fan of Ed D’Agostino’s YouTube interviews. This week, he had a particularly good guest whose interview caught my eye: Louis-Vincent Gave. If you are a Strategic Investment Conference fan like me, you know Gave. His interview with Ed is excellent. Put your sneakers on, plug your earbuds in, and head out for a walk (you’ll find the link to listen to it below).

Here are the sections in this week’s On My Radar:

- Understanding Cycles

- Louis Gave and Ed D’Agostino

- Random Tweets

- Personal Note: A Good Start to the Season

- Trade Signals: August Month-End Update

(Reminder: This is not a recommendation to buy or sell any security. My views may change at any time. The information is for discussion purposes only.)

If you are not signed up to receive the free weekly On My Radar letter, subscribe here.

Understanding Cycles

There are a lot of important studies on cycles. I’ve read The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest by Edward Chancellor, Principals for Navigating Big Debt Crises by Ray Dalio, Neil Howe’s books The Fourth Turning: An American Prophecy (with William Strauss)and The Fourth Turning Is Here, and George Friedman’s writing on cycles.

In John’s Thoughts From the Frontline letter last Saturday, August 26, he wrote about Peter Turchin’s new book, End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration. I’m sharing this most recent letter from John because, as Britt Harris put it, “It is what people need to know.”

To summarize, here’s the bottom line:

- We have a problem, and kicking the can down the road is nearing the end of the road.

- We have choices, but none are really very good.

- Dalio talks about “a beautiful deleveraging.” Think of it as a combination of debt reduction, money printing, debt monetization, higher taxes, QE, and reductions in pension, Social Security, and Medicare—all done in a way that takes the edge off of the extreme outcomes that will happen, ranging from depression on one end to extreme inflation on the other. His addition of “beautiful” somehow makes the restructuring we face less painful.

- Societies have reached this point before, but none, or very few, of us have ever experienced it, so we just don’t have it in our thought processes. But what is happening has happened many times before. The problem is the same mistakes tend to be repeated.

- Interestingly, all of the work done by the authors mentioned above points to the end cycle showing up in the latter half of this 2020s. It could be sooner, or it could be later.

- Personally, I have been obsessed with the work Ray Dalio and his team at Bridgewater have done. They have more resources than most. Hard to ignore what they have learned and are sharing with us.

- As they say, if there’s a storm bearing down on you and you’re prepared, you’ll be better able to survive the storm. Knowing what to look for as it builds and approaches is wise.

- Let’s keep watch on how the important players are responding (or not) to give us a better sense of timing and the severity of the outcome.

Resources:

- Watch: Neil Howe’s interview on the Julia La Roche Show discussing The Fourth Turning Is Here

- Read: Ray Dalio’s Principals For Navigating Big Debt Cycles

- Listen: The Price of Time, Edward Chancellor – Podcast interview

I share the full note from John next (you can subscribe to receive his free newsletter here).

The Science of Cycles

Today we continue our study of the historical cycles, suggesting a major crisis is in our near-term (5‒8 years) future. We don’t know the precise timing or nature of the crisis, but the patterns indicate one is coming and could be severe.

As with many therapeutic programs, the first step is admitting you have a problem. The good news is we have some time to think, reflect, and position ourselves to weather the coming storm, and with some luck, compromise and cooperation among leaders may even mitigate the problems.

So far, we’ve looked at Neil Howe’s Fourth Turning, a theory based on generational archetypes, and George Friedman’s idea of overlapping institutional and socioeconomic cycles. Both point to climactic events happening in the years around 2030. Today we turn to Peter Turchin, whose new book End Times uses more scientific tools to arrive at similar conclusions.

All three visionaries—an overused word but I think appropriate here—have their own ideologies and presuppositions. I know Neil and George quite well and am getting to know Turchin. (Full confession: While reading Turchin’s book I noticed what seemed to me a subtle left-leaning bias. Then I thought about Neil Howe’s book, and realized he has a right-leaning bias, which I didn’t notice at the time because I agreed with it. What would be surprising is no bias in talking about these fairly controversial ideas. In any event, both Howe’s and Turchin’s evidence massively overwhelms any bias.)

I think all three authors succeed in setting their own preferences aside, analyzing through their own informed lenses what they think will happen rather than promoting ideas of what should happen. I highly recommend all three books. Reading them may be the motivation you need to start preparing for what lies ahead.

Thoughts on Cycles

Before we look at Turchin, let me share some general thoughts. I always pay close attention to reader feedback (thank you!) and this series is generating a lot of it.

A number of readers are justifiably skeptical about historical cycles and models in general. I’ve often had similar thoughts about various economic and financial cycles (the Kondratiev Wave comes to mind).

The first and correct criticism is, I think, a misunderstanding of what the authors are trying to do. These forecasts by Howe, Friedman, and Turchin (and my own) are neither precise nor specifically predictive. No one is claiming to be Nostradamus here. We don’t know the future and many different things can happen. The possibilities are endless. What would another pandemic look like? Or a reproducible Fountain of Youth (perhaps closer than you think)? I am sure if you and I sit down together we can come up with a dozen different major events which could dramatically reshape the future.

But as I read these books, I saw patterns coinciding with my own observations of the world around us, admittedly viewed from a different lens of economic cycles. Does anyone really feel like we aren’t moving toward some kind of crisis in our culture, economy, and politics? That’s an even harder position to defend.

The value of these ideas is not that they tell us exactly what will happen, but the insight they give us into what might happen. I see them as signposts on the way to what all indicate will be a better period after the crisis. Our goal is to get there as intact as we can. Their work and thoughts can help us plan and be more aware of what will shape the future.

It’s also important that these multiple viewpoints, from greatly different disciplines, seemingly coincide in the same time period with the same endpoint of crisis. And in their own individual analyses, they realistically—if uncomfortably—describe where we are today. Their reasons coincide with what we all generally expect: growing problems and the potential for a crisis.

Here in Puerto Rico, we pay attention to hurricane warnings. Sometimes it is a problem and sometimes it’s not, but only the foolish fail to prepare on the assumption it is real.

In these books, we have multiple sources giving us the equivalent of a category 5 hurricane warning. I think we should pay attention.

Cliodynamics

Peter Turchin has a different perspective than Howe or Friedman. First, he was born and grew up in the Soviet Union, giving him personal experience with a culture and politics quite unlike what we know in the West. He doesn’t have to imagine what radical change is like. He has seen it. It of course produces a personal bias or understanding of history, but it is one that I find informative. My youth in West Texas helped form my own biases, but far closer to the norm than Turchin’s.

More important, Turchin is a scientist, a PhD-holding biologist and emeritus professor at the University of Connecticut. It was actually his study of insect populations that led him to patterns of human history. Why does a certain species of beetle, for instance, appear in a particular place, thrive for a while, and then almost disappear? Often it relates to the resources available in that place and how they are distributed among the insect population.

Turchin noticed something similar in human history. Societies emerge, thrive, and disappear to be replaced by something else. There’s a rhythm which repeats often enough to be considered a cycle. Turchin began collecting data to quantify this pattern, with the help of an increasingly large and diversly educated team which ultimately led to what he calls “cliodynamics,” an attempt to apply mathematical models to the development of human societies. Quoting [throughout this letter and in general I use backets […] to indicate I am inserting an idea or clarification into their words]:

“I began to consider how the same complexity science approach [on insect population] could be brought to the study of human societies, both in the past and today. A quarter of a century later, my colleagues in this endeavor and I have built out a flourishing field known as cliodynamics, (from Clio, the name of the Greek mythological muse of history, and dynamics, the science of change).

“We discovered that there are important recurring patterns, which can be observed throughout the sweep of human history over the past 10,000 years. Remarkably, despite the myriad of differences, complex human societies, at base and on some abstract level, are organized according to the same general principles. For skeptics and those simply curious, I have included a more detailed general account of cliodynamics in an appendix at the end of this book [which is fascinating].

“From the beginning, my colleagues and I in this new field focused on cycles of political integration and disintegration, particularly on state formation and state collapse. This is the area where our field’s findings are arguably the most robust—and arguably the most disturbing. It became clear to us through quantitative historical analysis that complex societies everywhere are affected by recurrent and, to a certain degree, predictable waves of political instability, brought about by the same basic set of forces, operating across the thousands of years of human history. It dawned on me some years ago that, assuming the pattern held, we were heading into the teeth of another storm.

“To put it somewhat wonkily, when a state, such as the United States, has stagnating or declining real wages (wages in inflation-adjusted dollars), a growing gap between rich and poor, overproduction of young graduates with advanced degrees, declining public trust, and exploding public debt, these seemingly disparate social indicators are actually related to each other dynamically. Historically, such developments have served as leading indicators of looming political instability. In the United States, all of these factors started to take an ominous turn in the 1970s. The data pointed to the years around 2020 when the confluence of these trends was expected to trigger a spike in political instability. And here we are.”

Regular readers know I am highly skeptical of models in general, particularly economic models. They tend to work until they don’t. This is usually because the economy changed in some important way. Turchin’s models are somewhat less prone to that flaw because their roots are in human nature which (sometimes sadly) has been quite stable for multiple millennia. Our species, while superior in many ways, is in certain respects predictably weak and foolish.

In 1979, Kahneman and Tversky created the foundations for the current analysis of behavioral economics. One of their conclusions was that humans are irrational [at least in their economic behavior], but the point is that they are predictably irrational. Turchin, et al., highlight yet another way in which human beings are sociologically predictable. Same song, different verse.

Turchin noticed societies always seem to split into elites and commoners. You might call the second group peasants or workers. In earlier ages they included serfs or even slaves. Today’s middle and lower classes have lives immeasurably better than serfs and peasants of the past, but nonetheless there is a difference between them and what passes as elites today. Whatever the label, upper and lower classes develop.

What makes one an elite? Two things: wealth and education, which are foundational to the power equation. These are the keys to a more comfortable life, so of course everyone seeks to achieve them. But not right away; in a society’s early development, the common people are generally satisfied—enough so that they produce many children. Their numbers grow and eventually resources become scarcer.

The scarce resources then get more expensive, to the benefit of the elites who own them. They become even more wealthy, and their numbers also grow. This “elite overproduction” is the beginning of the crisis. It spawns competition among elites who feel entitled to the advantages of their class. Inevitably some lose, falling down the scale while the top of the pyramid grows ever more elusive and distant. Some are radicalized into what Turchin calls “counter-elites” who oppose the ruling elites.

Meanwhile, with the elites consuming more and more economic resources, the commoner class becomes “immiserated,” unable to advance no matter how hard it works. Note this is relative. While a poor class person in the developed world may be immeasurably better off than the poor in Africa or Asia, they don’t compare their situation to poverty abroad but to the wealth that surrounds them. At this stage, they often see little opportunity to acquire their own wealth or at least advancement.

This unstable situation can persist for a long time, not unlike the financial system “sandpile” metaphor I’ve described. In this case, the sandpile collapse is triggered when a split develops within the elite class, giving the counter-elites and immiserated commoners an opportunity to exploit. Crisis follows, then the cycle starts again. This whole process tends to repeat every 50 years or so.

(If all that sounds a bit too neat, please read the book. I just compressed several chapters into a few paragraphs. Turchin describes it all in detail and gives many fascinating historic examples.)

Wealth Pump

The economic heart of this process is what Turchin calls the “wealth pump.” That’s the mechanism by which elites gain increasing control of assets while wages and wealth decline for everyone else. Understanding this is key to everything else, and particularly how the process is playing out right now in the United States.

Here, I’ll let Turchin speak for himself. This excerpt comes from chapter 8 of his book. (While this chapter is a summary, I think it is the most important. You should at least read it, and then maybe go back and look at the data that he builds his case on.)

“The wealth pump has a major effect not only on the commoner compartment (causing immiseration) but also on the elite compartment. Elite numbers change as a result of demography (the difference between birth and death rates), but this is a relatively unimportant factor for us because demographic rates between the elites and the commoners are not that different in the United States… The more important process is social mobility: the upward movement of commoners into the elite compartment and the downward movement of elites into the commoner compartment. And whether net mobility is upward depends on the wealth pump.

“The mechanism here is simple. When corporate officers [or entrepreneurs] keep increases in worker wages slower than the growth of the company’s revenues, they can use the surplus to give themselves higher salaries, more lucrative stock options, and so on. The CEO of such a company, upon retirement with a ‘golden parachute,’ becomes a new centimillionaire or even billionaire…

“This dynamic can also operate in reverse. When worker wages increase faster than GDP per capita (that is, when relative wages grow), the creation of new super rich is choked off. Some exceptional individuals continue to create new fortunes, but their numbers are few. The old wealth, meanwhile, is slowly dissipated as a result of bankruptcy, inflation, and division of property among multiple heirs. Under such conditions, the size of the superwealthy class gradually shrinks.

“But such a gradual, gentle decline assumes that the social system maintains its stability. Analysis of historical cases indicates that the much more frequent scenario of downward social mobility, which eliminates elite overproduction, is associated with periods of high sociopolitical instability, the ‘ages of discord.’ In such cases, downward mobility is rapid and typically associated with violence.

“Political instability and internal warfare prune elite numbers in a variety of ways. Some elite individuals are simply killed in civil wars or by way of assassination. Others may be dispossessed of their elite status when their faction loses in a civil war. Finally, general conditions of violence and lack of success discourage many ‘surplus’ elite aspirants from continuing their pursuit of elite status which leads to acceptance of downward mobility.

“Thus, the heart of the MPF model [Turchin’s mathematical tool to analyze all this—JM] is the relative wage and the wealth pump that it powers. When the relative wage declines it leads to both immiseration and elite overproduction. Both, as we now know, are the most important drivers of social and political instability.”

This sounds hauntingly like 2020s America, but Turchin shows this process repeating itself many times in different civilizations. It is not unique to us. But that isn’t encouraging because it rarely ends well and often ends violently.

Let’s check his data. Turchin mentions a specific way to measure this process, what he calls “relative wages” or wages relative to GDP. He uses GDP as a rough proxy for wealth.

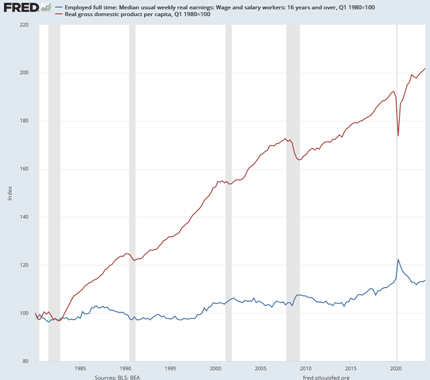

In the chart below the red line is GDP per capita (accounting for population growth and immigration). The blue line is median weekly earnings for full-time workers over age 16. Both are indexed so their 1980 level equals 100.

Source: FRED

As of mid-2023, per capita GDP had risen to 201.8 and wages were up to 113.7. GDP grew approximately seven times faster than wages. And note these are median wages, not average, so half the workers saw even less wage growth. This is what “immiseration” looks like.

Why start with 1980, you ask? Turchin sees that year as the previous cycle low. In his view, that’s when the elite class turned away from what had been relative generosity for the 50 prior years since the Great Depression. And we are now approaching 43 years into the next phase, hence the expectation of crisis soon.

From Turchin’s perspective, relative wages are key. If we are to avoid the worst-case outcomes, that gap between GDP and job earnings must start shrinking. Wages are indeed rising, especially at the lower end, but not nearly enough to close the gap anytime soon. Falling GDP would help but also create other, likely even more severe, problems. A few years of flat GDP might do the same thing, but we probably don’t have that time. Elite overproduction is out of control.

Remember, elites aren’t just the wealthy. The category also includes educated people, of which we have created many more in recent decades by making college degrees more widely accessible. We also created an expectation that these degrees would open the door to better lives. Yet the door stayed shut for many, and some of them aren’t at all happy about it. And especially with the massive student loans they used to chase the dream of rising into a high-paying job they felt they were promised if they only got that degree!

A US problem? Not at all. This is happening all over the world, though not everywhere. I am particularly thinking of China, where unemployment among young people is a minimum of 20%. Their parents sacrificed to send them to schools to get the right degrees, but in a slowing economy, those opportunities just don’t exist. Xi Jinping, with what sounds like a tone deaf ear, told them to be willing to go to the country to take a job. He asks them to help “revitalize” the countryside, which means take lower wages with less chance for promotion and improvement. Not what those parents and students thought they were signing up for. Sound familiar?

Turchin goes on to describe the conditions that lead to crisis outcomes. The good news is we are not yet beyond hope. There are ways we can avoid the worst, but certain groups will have to make some hard choices.

I’ll tell you more about that part next week.

SB Here: I’m looking forward to reading that next letter sitting in my beach chair tomorrow morning.

If you are not signed up to receive the free weekly On My Radar letter, subscribe here.

Louis Gave and Ed D’Agostino

Mauldin Economics COO Ed D’Agostino talks to Louis Gave, CEO of Gavekal Research, about China’s so-called economic crisis, the Fed’s unspoken third mandate, and “the real story of the summer.” You’ll also hear about Louis Gave’s top investment themes, the future of reshoring, and what the United States’ $30+ trillion debt train means for the US dollar.

You can learn more about Louis Gave here: https://research.gavekal.com/author/l… Stay informed on the big trends by subscribing to Global Macro Update here: https://www.mauldineconomics.com/go/J… Please stay in touch by following me on X (formerly Twitter) @EdDAgostino: https://twitter.com/EdDAgostino

Time stamps:

- Introduction: 00:00

- The world’s most important asset class: 01:03

- The Fed’s unspoken third mandate: 07:46

- China’s non-crisis: 12:20

- How China undermines US exceptionalism: 17:16

- Why deglobalization is a misnomer: 24:23

- What does the US get for $30+ trillion in debt?: 30:06

- Louis Gave’s top investing themes: 33:50

Not a recommendation to buy or sell any security. For discussion purposes only. Current viewpoints are subject to change.

If you are not signed up to receive the free weekly On My Radar letter, subscribe here.

Random Tweets

Bob Farrell’s Ten Rules – Always a good reminder:

1. Markets Return to the Mean Over Time

2. Excess Leads to an Opposite Excess

3. Excesses Are Never Permanent

4. Market Corrections Don’t Go Sideways

5. Public Buys Most at the Top and Least at the Bottom

6. Fear and Greed: Stronger Than Long-Term Resolve

7. Markets: Strong When Broad, Weak When Narrow

8. Bear Markets Have Three Stages

9. Be Mindful of Experts and Forecasts

10. Bull Markets Are More Fun Than Bear Markets

Source: For more information, click here.

Found this interesting. Soft Landing? I just don’t think so. The opposite is more probable:

Seven Stocks:

Source: @KobeissiLetter

Hat tip John Mauldin “Clips That Matter”

Personal Note: A Good Start to the Season

I wrote about “Adversity” last week and told a story about my favorite coach (my wife Susan) and the tryouts for her high school boy’s soccer team. I wrote about the third goalie contender who did not make the team. He’d been pretty upset about it, but Susan heard from the JV coach after their first practice that he’d been the best player out there. I knew I wanted to keep an eye on the kid after that.

And keep an eye on him, I did. After two successful preseason games, both varsity goalies were sidelined with injuries. As the team approached their season opener yesterday, the “kid,” was pulled up from JV to start the game. The boys won the game 4-0. As the team huddled afterward, one of the injured goalies spoke up. “Can we give a round of applause to the clean sheet?” he said. A “clean sheet” is when a goalie doesn’t let in a goal. Think about the pressure on the young man in that game, and he rose to the occasion. It was really fun to see.

I’m enjoying my volunteer coaching time and getting to know the new group of young men. And sitting next to my favorite coach, of course. The next game is Wednesday.

With the holiday weekend beginning, Susan and I will be heading “down the shore,” as they say here in Phila, to spend a day on the beach. Golf with friends is lined up for Sunday, and there’s much to do around the house on Monday. Next week, I’m in Nashville on Tuesday for a due diligence meeting and dinner, with an early flight on Wednesday to return home in time for the 4 p.m. soccer game.

Don’t let the economic outlook get you down. Find opportunities—there are many—in commodities, energy, oil, gold, agriculture, real estate, trading, and stocks (innovation/disrupters)… The bubble is in passive cap-weighted index funds and overvalued equities. The bubble is in distressed debt. The bubble is in government bonds. Avoid category five bubbles.

Wishing you a wonderful long holiday weekend!

All the very best!

Trade Signals: August Month-End Update

“Extreme patience combined with extreme decisiveness. You may call that our investment process. Yes, it’s that simple.”

– Charlie Munger

August 30, 2023: The long-term picture remains concerning. Valuations on cap-weighted indices remain way too high. There is a bubble in passive indices. Active stock selection is back. Sell (and/or hedge) the rallies.

August is finishing on a stronger note. After a sharp decline of more than 5% from the July 2023 high (4,607), the S&P 500 Index bottomed five trading days ago at 4,335. Rallying the last four days, it closed today at 4,514.

Investor sentiment reached a bullish extreme in July. It was a “Sell when everyone else is buying” moment. Investor sentiment is neutral today. Neutral is neutral. Use investor sentiment to identify extremes (turning points).

The short-term high-yield MACD is back in a buy signal. The short-term S&P 500 Index daily MACD is back in a buy signal. Both are quick trading opportunities.

The outlook for oil and gold remains bullish. The high-quality bond indicators remain in a sell. However, the Zweig Bond Model is improving, having moved from a –5 score to a –2 score this week. I’m watching the U.S. Treasury Yield MACD to signal the trend towards lower interest rates. Lower rates are bullish for interest rate-sensitive bonds.

If you believe a recession is nearing, a 30-year Treasury bond trade is shaping up nicely. But the bond indicators still need to be bullish. That is yet to be the case.

The oil and gold price trends remain bullish.

The dashboard of indicators follows. You’ll find the updated charts with the explanations section below.

The dashboard of indicators and the stock, bond, developed, and emerging market charts, along with the dollar and gold charts, are updated each week. We monitor inflation and recession as well. If you are not a subscriber and would like a sample, reply to this email, and we’ll send you a sample. The letter is free for CMG clients. You can SUBSCRIBE or LOGIN by clicking on the link below.

TRADE SIGNALS SUBSCRIPTION ACKNOWLEDGEMENT / IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The views expressed herein are solely those of Steve Blumenthal as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice.

With kind regards,

Steve

Stephen B. Blumenthal

Executive Chairman & CIO

CMG Capital Management Group, Inc.

Private Wealth Client Website – www.cmgprivatewealth.com

TAMP Advisor Client Webiste – www.cmgwealth.com

If you are not signed up to receive the free weekly On My Radar letter, you can sign up here. Follow me on Spotify, Twitter @SBlumenthalCMG, and LinkedIn.

Forbes Book – On My Radar, Navigating Stock Market Cycles. Stephen Blumenthal gives investors a game plan and the advice they need to develop a risk-minded and opportunity-based investment approach. It is about how to grow and defend your wealth. You can learn more here.

Stephen Blumenthal founded CMG Capital Management Group in 1992 and serves today as its Executive Chairman and CIO. Steve authors a free weekly e-letter entitled, “On My Radar.” Steve shares his views on macroeconomic research, valuations, portfolio construction, asset allocation and risk management.

Follow Steve on Twitter @SBlumenthalCMG and LinkedIn.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURE INFORMATION

This document is prepared by CMG Capital Management Group, Inc. (“CMG”) and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives, or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, CMG’s actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing, and transaction costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment, or other advice. The views expressed herein are solely those of Steve Blumenthal as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice.

Investing involves risk. Past performance does not guarantee or indicate future results. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product (including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended or undertaken by CMG), or any non-investment related content, made reference to directly or indirectly in this commentary will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation or prove successful. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this commentary serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from CMG. Please remember to contact CMG, in writing, if there are any changes in your personal/financial situation or investment objectives for the purpose of reviewing/evaluating/revising our previous recommendations and/or services, or if you would like to impose, add, or to modify any reasonable restrictions to our investment advisory services. Unless, and until, you notify us, in writing, to the contrary, we shall continue to provide services as we do currently. CMG is neither a law firm, nor a certified public accounting firm, and no portion of the commentary content should be construed as legal or accounting advice.

No portion of the content should be construed as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. References to specific securities, investment programs or funds are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as recommendations to purchase or sell such securities.

This presentation does not discuss, directly or indirectly, the amount of the profits or losses realized or unrealized, by any CMG client from any specific funds or securities. Please note: In the event that CMG references performance results for an actual CMG portfolio, the results are reported net of advisory fees and inclusive of dividends. The performance referenced is that as determined and/or provided directly by the referenced funds and/or publishers, has not been independently verified, and does not reflect the performance of any specific CMG client. CMG clients may have experienced materially different performance based upon various factors during the corresponding time periods. See in links provided citing limitations of hypothetical back-tested information. Past performance cannot predict or guarantee future performance. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Please talk to your advisor.

Information herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but we do not warrant its accuracy. This document is general communication and is provided for informational and/or educational purposes only. None of the content should be viewed as a suggestion that you take or refrain from taking any action nor as a recommendation for any specific investment product, strategy, or other such purposes.

In a rising interest rate environment, the value of fixed-income securities generally declines, and conversely, in a falling interest rate environment, the value of fixed-income securities generally increases. High-yield securities may be subject to heightened market, interest rate, or credit risk and should not be purchased solely because of the stated yield. Ratings are measured on a scale that ranges from AAA or Aaa (highest) to D or C (lowest). Investment-grade investments are those rated from highest down to BBB- or Baa3.

NOT FDIC INSURED. MAY LOSE VALUE. NO BANK GUARANTEE.

Certain information contained herein has been obtained from third-party sources believed to be reliable, but we cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness.

In the event that there has been a change in an individual’s investment objective or financial situation, he/she is encouraged to consult with his/her investment professional.

Written Disclosure Statement. CMG is an SEC-registered investment adviser located in Malvern, Pennsylvania. Stephen B. Blumenthal is CMG’s founder and CEO. Please note: The above views are those of CMG and its CEO, Stephen Blumenthal, and do not reflect those of any sub-advisor that CMG may engage to manage any CMG strategy, or exclusively determines any internal strategy employed by CMG. A copy of CMG’s current written disclosure statement discussing advisory services and fees is available upon request or via CMG’s internet web site at www.cmgwealth.com/disclosures. CMG is committed to protecting your personal information. Click here to review CMG’s privacy policies.